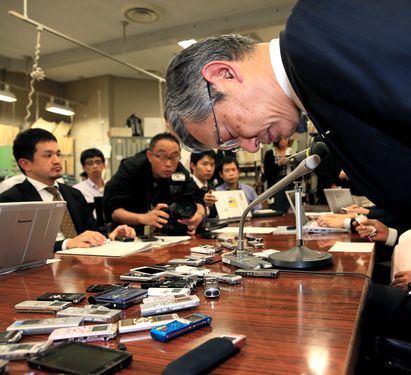

Deputy President of Mizuho Bank Toshitsugu Okabe apologizes at a press conference following a string of loan scandals involving the yakuza. © Hikaru Uchida/Asahi Shimbun

Sokaiya is the name of a form of large-scale bribery practiced by the yakuza. First, the yakuza purchase just enough shares to be invited to the annual shareholders meeting. Then, they dig up as much dirt on the executives of the company – love affairs, failed businesses, unsavory relations – and threaten to expose them at the meeting, demanding bribes in exchange for silence. One particularly brazen form of sokaiya is banzai sokaiya. This is when an individual or group buys a few shares in the company, then raids the business premises shouting “Banzai”, the Imperial rallying call. When asked to stop, the individual responds that as a shareholder he is simply trying to increase worker enthusiasm and productivity. To avoid any further embarrassment, the company will usually quickly bribe the person on the spot.[i] This practice takes advantage of Japan’s culture of shame. Embarrassment of any form is considered failure in Japanese culture, and Japanese companies will try to avoid shame at all costs.[ii]

Some of Japan’s largest companies have been targeted by sokaiya. A survey of some 2000 companies in 1992 revealed the 41% had been approached or threatened by yakuza, and of those approached, 30% had given in to the yakuza demands to avoid further shame. Surprisingly, the larger the company, the more like the yakuza are to target them. 70% of the companies surveyed had annual sales of over $1 Billion.[iii] The bribes are usually hidden on the corporate balance sheet in the form of donations to charities or gold club memberships. The yakuza will host an event—a golf tournament or beauty pageant, for example—and sell awfully overpriced tickets to the victims of their blackmail.[iv]

Sometimes, sokaiya are hired by companies to keep their shareholders meetings quiet. The sokaiya show up with cropped haircuts and flamboyant ties, and proceed to shout down or intimidate legitimate shareholders who may ask embarrassing questions. The Chisso Corporation, a fertilizer company with a factory in Minamata, Japan, infamously hired sokaiya. The Chisso factory released toxic mercury in to the bay, leading to the “Minamata disease”, or mercury poisoning, to present itself among some 2000 victims.[v] The Chisso Corporation installed sokaiya in their meetings to intimidate shareholders, and even had the yakuza beat up several victims.[vi] In 1993, four executives from the Kirin Brewery Company were arrested on the grounds of paying sokaiya $300,000 to smooth the shareholders meeting. The year before, Ito-Yokodo Company, a large retailer, had three executives arrested for paying $200,000 for similar reasons.[vii]

Sokaiya really thrived during the Japanese economic bubble. By 1982, sokaiya had reached such endemic proportions that Japan officially outlawed it.[viii] While this certainly decreased sokaiya instance number at shareholder meetings, yakuza began to find other methods of extorting companies.[ix] For example, some yakuza formed fake extreme right-wing political groups, known as uyoku dantai, and park trucks in front of the companies, blaring rhetoric about the corporation until they are paid off.[x] One of the only effective measures against sokaiya has been to hold shareholder meetings on the same day, since there are only so many yakuza that can attend a single meeting. At one point, 95% of companies on the Tokyo Stock Exchange held their shareholder meetings on the same day. Unfortunately, this tactic works against the shareholders as well, with many shareholders only attending 1 or 2 meetings.[xi]

Another massive source of yakuza revenue, especially during the bubble years, are jiageya. Jiageya are people (often yakuza) who forcibly evict tenets from their homes and bundle up the properties to make way for larger commercial projects. In Japan, there are strong tenant’s rights and weak laws regarding eminent domain, so people with “stronger” forms of persuasion, mainly yakuza, were needed to evict the tenets.[xii] Sometimes even the government would indirectly use Jigaeya. Jigaeya had many methods they would use to force homeowners to leave. These included blaring loud music, smearing manure on the buildings, breaking windows, even arson.[xiii]

During the bubble years, real estate prices soared, and many yakuza took advantage of this boom. Yakuza were often financed by big banks, which saw the real estate projects as lucrative opportunities for investment. Some banks even formed closer relationships with the yakuza, using their underground connections to dig up dirt on rival firms. Apparently even the yakuza were surprised by the big banks’ lack of morality; the yakuza live by a moral code, and many believe what they do to be just.[xiv] When the bubble burst, real estate prices plummeted and banks were left with over $800 billion in bad loans. Researchers estimate that as much as 80% of the defunct loans were connected to yakuza, much higher than the already ridiculous government estimate of $400 billion.[xv]

It is clear that yakuza are deeply entrenched in both Japanese political and corporate culture. Historically, the yakuza have been linked to extreme right-wing political groups, known as uyoku dantai, due to their strict samurai like values and vicious anti-communist sentiment. Of the 900-odd uyoku dantai groups, with some 10,000 members, police estimate half are fronts for yakuza organizations.[xvi] Yakuza and politics go way back. Former Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi, current Prime Minister Abe’s grandfather, famously bailed out a leader of the Yamaguchi-gumi later convicted of murder, and had regular dinners with yakuza members.[xvii] Susumu Ishii, oyabun for the Inagawa-kai, allegedly helped Prime Minister Noboru Takeshita get elected by silencing the uyoku dantai trucks that would disrupt his campaign events.[xviii] Ishii, known as the “economy yakuza”, also made hundreds of millions of dollars by buying shares Tokyu, a major railway operator. He leveraged his connections with Nomura Holdings and Nikko, who then recommended Tokyu stock on their clients, pushing the stock price up by over 30%.[xix] More recently in 2012, Keishu Tanaka, the then-justice minister, stepped down following just three weeks in office after a magazine exposed his previous contacts with yakuza members.[xx]

[i] McCarthy, Terry. “Japan Gangster Takes Airline for Costly Ride.” Editorial. n.d.: n. pag. The Independent. Independent Digital News and Media. Web. 14 Dec. 2015.

[ii] Maruko, Eiko. “Ejcjs – Sokaiya and Japanese Corporations.” Ejcjs – Sokaiya and Japanese Corporations. Electronic Journal of Contemporary Japanese Studies, 25 June 2002. Web. 14 Dec. 2015.

[iii] McCarthy, Terry. “Japan’s Crime Incorporated: The Years of the Bubble Economy Lured Japan’s Yakuza Gangs to Muscle into Big Business. Terry McCarthy in Tokyo Explores Their Corporate Web.” Editorial. n.d.: n. pag. The Independent. Independent Digital News and Media. Web. 14 Dec. 2015.

[iv] Wathen, Mel. “Sokaiya– Extortion Protection & the Japanese Corporation.” Japan Society. Japan Society, n.d. Web. 14 Dec. 2015.

[v] “Minamata Disease: Methylmercury Poisoning in Japan Caused by Environmental Pollution.” National Center for Biotechnology Information. U.S. National Library of Medicine, n.d. Web. 14 Dec. 2015.

[vi] McCarthy, Terry. “Japan Gangster Takes Airline for Costly Ride.” Editorial. n.d.: n. pag. The Independent. Independent Digital News and Media. Web. 14 Dec. 2015.

[vii] Pollack, Andrew. “Where Meetings Are Truly Feared.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 27 June 1994. Web. 14 Dec. 2015.

[viii] Boyle, Alan. “10 Odd Facts About The Yakuza – Listverse.” Listverse. Listverse, 22 Oct. 2013. Web. 14 Dec. 2015.

[ix] McCarthy, Terry. “Japan’s Crime Incorporated: The Years of the Bubble Economy Lured Japan’s Yakuza Gangs to Muscle into Big Business. Terry McCarthy in Tokyo Explores Their Corporate Web.” Editorial. n.d.: n. pag. The Independent. Independent Digital News and Media. Web. 14 Dec. 2015.

[x] Maruko, Eiko. “Ejcjs – Sokaiya and Japanese Corporations.” Ejcjs. Electronic Journal of Contemporary Japanese Studies, 25 June 2002. Web. 14 Dec. 2015.

[xi] Wudunn, Sheryl. “Prying Open the Japanese Shareholder Meeting.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 27 June 1996. Web. 14 Dec. 2015.

[xii] Adelstein, Jake. “Types of Yakuza and Their Businesses : Japan Subculture Research Center.” Japan Subculture. Japan Subculture Research Center, 6 May 2012. Web. 14 Dec. 2015.

[xiii] David, Holley. “Japan Mob Muddies Real Estate Loan Crisis.” Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times, 24 Feb. 1996. Web. 14 Dec. 2015.

[xiv] Ibid.

[xv] “The Yakuza And The Banks (Int’l Edition).” Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg, n.d. Web. 14 Dec. 2015.

[xvi] “Old Habits Die Hard.” The Economist. The Economist Newspaper, 19 May 2007. Web. 14 Dec. 2015.

[xvii] Adelstein, Jake. “Learning Valuable Lessons from the Yakuza? | The Japan Times.” Japan Times. The Japan Times, n.d. Web. 14 Dec. 2015.

[xviii] Sterngold, James. “Mob and Politics Intersect, Fueling Cynicism in Japan.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 20 Oct. 1992. Web. 14 Dec. 2015.

[xix] McCarthy, Terry. “Japan’s Crime Incorporated: The Years of the Bubble Economy Lured Japan’s Yakuza Gangs to Muscle into Big Business. Terry McCarthy in Tokyo Explores Their Corporate Web.” Editorial. n.d.: n. pag. The Independent. Independent Digital News and Media. Web. 14 Dec. 2015.

[xx] McCurry, Justin. “Japan Justice Minister Quits over Yakuza Links.” The Guardian. Guardian News, 23 Oct. 2012. Web. 15 Dec. 2015.